Ornette Coleman’s Big Adventure

August 29, 2012

By Richard Brody

The restoration and reissue of “Ornette: Made in America,” Shirley Clarke’s 1985 portrait of Ornette Coleman, the saxophonist whose recordings and performances in the late fifties and early sixties were among the most liberating avant-garde breakthroughs in the history of jazz (and who, happily, is still performing, at the age of eighty-two), is cause for celebration—both for its value as a movie and for its exploration of Coleman’s art. I’ve got a capsule review in the magazine this week about the movie (above is a clip). There’s a lot more to say about it, particularly regarding the way that Clarke uses video technology and dramatic reconstructions to evoke Coleman’s way of thinking, but here I’d like to focus on Coleman’s music—which I’ve been passionate about since I was in high school, in the seventies, and still listen to enthusiastically—while noting the ways in which the movie contributes to a better understanding of the music.

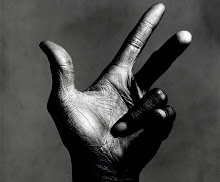

One way into Coleman’s music is to think of it as avant-gutbucket. Hailing from Fort Worth (which figures prominently in the film, as in the clip ), he got his start in rhythm and blues and the blues are, conspicuously, at the forefront of his achievement. (In the movie, he speaks warmly of another son of the city, King Curtis, who, having made a fortune from a more popular strain of bluesy jazz, picked Coleman up in New York with his Rolls-Royce.) The forbidding harmonic intricacy of bebop sparked several responses in the fifties, but Coleman’s was the most radical. He threw out the chord changes, famously excluding pianists from his primordial groups, thus eliminating “comping,” or chord-prompting that kept soloists in line, and played music that often had the furious speed of bop but lacked its tonal anchors. His melodies and solos were filled with catchy bluesy riffs and soul-chilling cries, but he shifted notes (or, rather, from pitches) without regard for traditionally recognizable relations of consonance.

That’s why, when he came to New York, in 1959, Coleman was instantly considered an enfant terrible who brazenly imported something like atonality into jazz. But what really made his style catch on was that his phrases were, in fact, fluently, melodically, catchily, deep-in-the-bone singable—close in feel to the primal wails of blues singers. Coleman wasn’t so much against harmony as he was questioning it; wasn’t opposed to chords (he employed marvellous bass players, including Charlie Haden, who’s seen in this clip) but to constraints; and, as his solos took flight, they were received as signal acts of modernism, exposing the conventions of jazz while defying them, turning jazz performance into an act of spontaneous thought, constant musical invention, and self-questioning. What made his 1959 performances seminal moments of free jazz was the very idea of freedom that they embodied.

The boxed set of recordings that Coleman made for Atlantic between 1959 and 1961 is a cornerstone of jazz history. If I was constrained to pick one album, it would be the first “The Shape of Jazz to Come,” which opens with the frenetic quadruple-time dirge “Lonely Woman,” one of the most covered jazz compositions, and includes the fragmented “Focus on Sanity,” the lyrical “Peace,” and two loping rockers that highlight Coleman’s emotionally straightforward sense of swing. My second choice would be “This Is Our Music,” featuring the rollicking jitter of Ed Blackwell’s drumming. (Sample “Blues Connotation” for the tuneful pole of Coleman’s playing, sample “Folk Tale” for the unmoored and impulsive one.)

At the end of the clip, Coleman, tells his son, Denardo, “What really makes me want to play music is when I really hear an individual thought pattern placed in an environment to make something actually come about that is not an obvious thing that everyone is doing.” It’s a serious remark that gets to the heart of Coleman’s project—context is essential to his music. His style of playing hasn’t changed drastically since he got started, but his music has nonetheless evolved greatly by means of his changing groups and settings. He emerged with a quartet featuring the trumpeter Don Cherry, plus the bassist Charlie Haden and the drummer Billy Higgins, then Blackwell and the short-lived bassist Scott LaFaro; he then jettisoned the quartet for a trio (David Izenzon and Charles Moffett). A live 1962 performance points far ahead, with a twenty-three minute excursion through a labyrinth of tones, themes, tempi suggests the search for an even more fluid musical framework as well as a string quartet, composed by Coleman, that suggests the growing desire to shift contexts drastically and bypass the traditions of jazz altogether.

Two wonderful volumes of that trio, live from Sweden in 1965, are available, and the sound is much better than the 1962 issue. The second volume (which has the exquisitely tender “Morning Song” and “Antiques”) features a cut with Coleman playing violin and trumpet, neither of which is really his instrument. But, of course, he does indeed play them, and the very notion of performing on instruments on which he’s less than a complete master is a conceptual act of a high order. He was creating sounds that owe less to virtuosity than to gesture, less to skill than to will. Though the lack of variety and nuance makes his brevity on them welcome, those instruments and the sound he conjures with them have became a small but crucial part in his music.

The following year, he took an even stranger leap into the conceptual: he replaced his drummer with his son, Denardo, who was ten years old, for the album “The Empty Foxhole”—six tracks, three on alto, two on trumpet, one on violin. Coleman made himself, in effect, into as much of a beginner as his son was. The video clip above shows them performing together two years later, in 1968. The results were remarkable, precisely because, as Denardo was finding his way into his instrument, the role of the drums became more ornamental and coloristic. (This compilation includes two tracks from it, “Zig Zag” and “Good Old Days.”) Within a few years, the rumble and bash of Denardo’s drumming became one of Coleman’s constants (they play together to this day), and one of Coleman’s best albums, “Crisis” (sadly unavailable), live from N.Y.U. in 1969, displays the emotional range of his newly protean group concept.

The orchestral composition “Skies of America,” recorded in 1972, is also performed by Coleman and his band in Clarke’s film. That group went through a drastic change in the mid-seventies: Coleman added electric guitars (including that of James “Blood” Ulmer), electric basses, and sometimes a second drummer, but, despite the rockish tones, the music is as adventuresome and free as ever. He called this group Prime Time; they’re in the film, but most of their finest albums (including “Of Human Feelings” and “In All Languages”) are unavailable. There are some wonderful video clips floating around (here’s one from Germany in 1978 and one from Montreal in 1988). The first recording he made with this group, “Dancing in Your Head,” is still a shock (it includes performances he gave in Morocco with Joujouka musicians, a story that Clarke tells). For all the recording’s electrical energy and off-kilter harmonies, it’s centered on an almost childlike ditty that has remained something of an obsession of Coleman’s for more than forty years.

One of the crucial revelations of Clarke’s film is the utopian aspect of Coleman’s music. The progression from a quartet to a string quartet to a symphony orchestra to a rock band is only a small part of his striving to take the music out of its original context in clubs and studios. The movie documents a satellite-video project, an attempt to turn an abandoned school on Rivington Street into an art space, and a performance in a geodesic dome (Coleman cites Buckminster Fuller as a lifelong hero). Music is a subset of sound, which is a subset of life, and Coleman’s implicitly philosophical ambition has always been to make explicit the unified field of creation and of life. Interviewed in this magazine in 1960, he said, “It’s the hidden things, the subconscious that lies in the body and lets you know: you feel this, you play this.”

Childhood recollections and sophisticated theories, electronics and primal cries, silent reflections and collective revelries, symphonic grandeur and down-home mother—for Coleman, music has never been quite enough to contain and to reflect the unfathomable depths of his experience. He has been performing furiously all his life even while clawing at the scrim that music has placed between him and others. It’s exactly this tension, the striving toward immediate and terrifyingly risky connections, that has made Coleman’s music more than music, and has made him one of the great creative adventurers of the century.

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/movies/2012/08/ornette-coleman-on-disk-and-screen.html

Ornette: Made in America : A Film by Shirley Clarke (Official Trailer)

![Emilio Aragón [Miliki]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgU984UtiH44tEevrjWKEP26uzJpkSR0NMPCyUzIg16SRop9lUziLazCa4V3Ol9LgmRdnzgHiyLD-8SPVx7J7cZt1G5jmzE1lDfWyzlvXaq7dp2EQ5OLle-bBG3ZcovVu5h00ZzuOwXVCo/s220/Gracias+Miliki%2521.jpg)